We have a strange desire for control.

I was in a planning meeting with my project manager and several of the devs. “What happened?” the project manager said. “Why did this one story take so long?”

“There was some functionality we needed and didn’t know about,” I replied. “We managed to get it in before the deadline, though.” The business had been quite happy with that, and they were notoriously hard to please.

“If they’re going to change their mind like this,” the PM replied, “we’re going to have to introduce some kind of change control.”

“Please don’t,” I begged. “If you do that, the business will spend more time investing in getting things right to start with.”

“Exactly.”

“But they’ll still get it wrong. No amount of planning would have spotted that missing piece before we showed it to them! When they get it wrong now, though, they’ll encounter the change control and they’ll want to spend even more time getting it right first time. And they’ll still get it wrong, but now we’ll have made it more expensive for them to be wrong. We’ll have a formal process which means it takes even longer for us to find out what’s missing, by which time us devs will have to work to remember the code and the change will take longer. It will slow us down. So they’ll see that, and spend even more time trying to get it right, and before you know it they’ll be planning whole projects up front.”

We have a word for that. It’s called Waterfall.

That desire to control change creates a reinforcing feedback loop, in which the cost of change makes us want to invest up-front, which makes the change expensive later on, which makes us want to invest up-front, and so on.

In this case, it would have been pointless, except as a way of shifting blame and risk back to the analysts (and this was an internal project). The cost of change was quite low; we had clean code with a good suite of tests. It was only the cost of discovery, and the implementation that followed, that was really expensive.

Don’t confuse the cost of discovery with the cost of change.

Discovering something later on only costs more than planning for it if you’ve made a commitment to something else.

In fact, if you don’t plan for it, it can cost less. The newly-discovered knowledge will be fresh in everyone’s minds. Because the ideas haven’t been known for long, nobody’s mentally committed to them either, which makes them easier to question and clarify.

This is even more important when there’s a chance that the analysis might be wrong (and there’s always that chance; we learnt this from Waterfall). If you plan for something that you later have to revert, you’ve introduced a cost of change right there. Perhaps the cost is just changing some documents. Perhaps the developers have designed for the plan, and built on top of the thing which needs changing.

But we need to do some planning, right? Otherwise the chances of us being wrong and building on top of the wrong thing are even bigger, and there’s even more chance that we’ll have made commitments the wrong way. So how should we plan?

I’ve got few more guidelines I’d like to share. Here’s the first:

Keep the cost of change low.

This is more important even than planning, because there’s always a chance that we’ll get something wrong.

This is what we’re aiming for: the ideal, low cost of change on an Agile project.

The first thing to notice about this is that the cost of change is not zero. That’s going to become important in the next section, and it’s what drives the team’s desire for change control and starts kicking off that Waterfall loop.

The second thing to notice is that this bears little resemblance to actual, real Agile projects.

On a real Agile project, it’s likely that we have fluctuating levels of stress, concentration, experience and desire for feedback. All of these – or lack of them – will lead us to occasionally write code that is, shall we say, less than ideal.

It takes discipline to write code that’s easy to change. On a real Agile project, we tend not to do it all the time. Oh, we might say we do, but we don’t. Not always. And if we do, our team-mates don’t. The real skill isn’t in writing clean code – it’s in cleaning up the horrible mess we made the week before. And it takes even more discipline to do it afterwards, especially if you’re under pressure to just hack the next working thing in too.

If we don’t clean up and keep that cost of change low, we’re making a commitment to the wrong thing. The longer that commitment stays in place, the higher the cost of change will become. We’ll find ourselves on that Waterfall cost of change curve, and the longer we’re on it, the more expensive it is.

I’ve found the skill to clean up afterwards is even more important in high-learning projects, where a lot of the technology or domain is new, at least to the team. There’s no point in writing tests up front for a class when you don’t even know what’s possible, or what other frameworks and libraries will do for you, or what the business really want. In those environments, rather than TDD or BDD, teams tend to Spike and Stabilize. The spikes aren’t really prototypes – they’re small pieces of features, often with hard-coded data behind them, designed to get some feedback about techology or requirements. Dan North, who gave me the term, might write more about this later if we ask nicely, but for this post, we can simply bear in mind that the skill to stabilize later – ensuring that the cost of change is lowered – is often more important than the skill to keep the cost of change low up-front.

Because we get it wrong too.

Assume you got it wrong.

Human beings are hard-wired to try and get things right, and to pretend that they did even when they didn’t. I love this list of cognitive biases on Wikipedia. These are just some of the ways in which we get it wrong and don’t even notice.

If we assume that we got it wrong, then we start to look for feedback, and quickly. This is difficult for most human beings. We much prefer to get validation than feedback; to be told that we did it right, rather than finding out what we did wrong. Our brain gives us these little kicks of nice chemicals when we learn that we did something right, and it feels much better than the other kind.

If we can remember, though, that we probably got it wrong, our focus will change. Instead of trying to invest in good requirements and nice code, we’ll try to find out what we got wrong in the things we’ve already done. Of course, we need to invest in stabilizing what we’ve done, or the cost of change goes up, and that will make it more expensive later if we find out we were wrong, which is the assumption we were trying to make in the first place… ah, the paradox!

There’s a fine balance to be struck between getting quick feedback – often itself an expensive proposition, given the business of most domain experts – and getting it right up front. So where does the balance lie?

Don’t sweat the petty stuff.

If it’s easy to change, don’t worry about it. Analysts, learn what’s easy to change. Typos, colours, fonts, labels, sizes, placement on the screen, tab order, an extra field… these are all usually easy to change, and do not normally need to be specified up-front. Even if you have a particular style you want to see on a page or form, this can usually be abstracted out and changed later – just let the devs know that you want that consistency at some point.

It’s more important for us to know the rough shape of what you want to see, and the flow and process of that information. We don’t want to know every field on an order item. We just want to know that it needs to be sent to the warehouse and stored locally because you’re going to check the money in the till and count the stock. The fine detail of that is pretty easy to change, so we can get feedback on it later. Getting the fine detail right would definitely be an investment, and we might have got the big picture wrong.

Deliberately discover things you’ve never done before.

Dan North wrote an excellent post on Deliberate Discovery, and I’ve been using it to manage risk on my projects for a while now. It’s one of the most important tools in my toolbox, along with Real Options to which it’s strongly related, so I want to cover how I use it here.

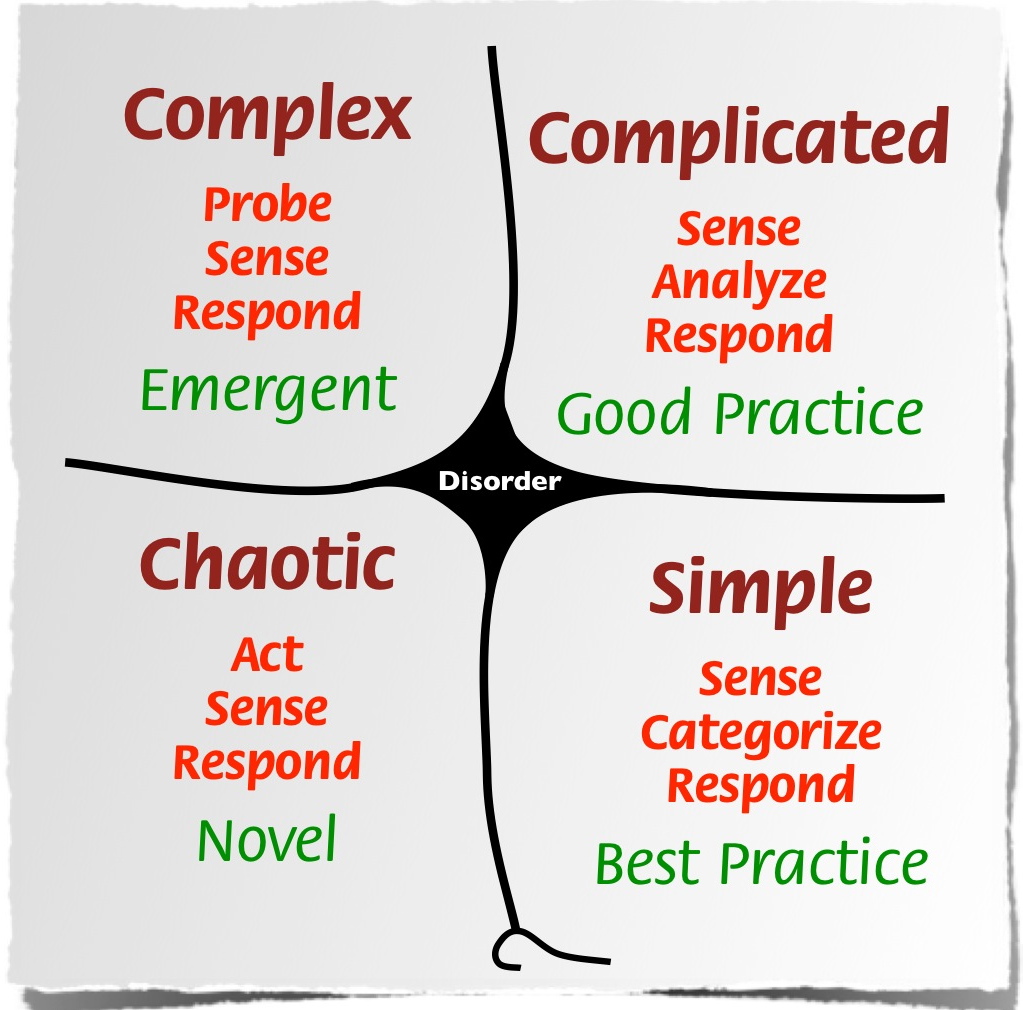

I really like using Cynefin to help me work out what to target for discovery. We treat a lot of software as if it’s complex, and we talk about self-organising teams and high learning environments, but in reality there are huge chunks in most applications which follow well-established rules, have been done a thousand times before and probably have libraries or third-party apps to do the job for you. They’re not complex. They’re complicated. They require the application of a bit of expertise, and are likely to be done right and never changed again. User registration and logging in are great examples of this. You don’t need a big, thick document to describe them. The fine details might change, of course, but we already know not to sweat the petty stuff.

It is OK to plan some aspects of a system as if it’s Waterfall – for instance, deciding up-front whether you want to use your own login or let Google authenticate. Even better than requirements documents, and quicker, is to say, “It’s user registration. Make it work like Twitter’s, but we also need the user’s loyalty card number. We should offer to send them a card if they don’t have one.” Dan North calls this pattern “Ginger Cake” – it’s like a chocolate cake, but with ginger. He even cuts and pastes code. And it’s OK! Honestly, it is! This code is also absolutely prime for TDDing – if you actually have to write it yourself, that is, since it’s been done before so someone’s probably written something to do it for you already. You can also give this code to junior devs, for whom it’s new, and guide them in TDDing, making it perfect pair-programming territory. Everything you have ever been told about Agile software development applies particularly in this place.

Fortunately, most applications have a minimum set of requirements that they share with other, similar applications. David Anderson calls these commodities – table stakes that you have to have just to play the game – so *most* code in an application will end up going this way.

The places in which we’re most likely to get it wrong, and need fast feedback, are places where we’re doing something new. They might be technological, particular to a domain, or just things that the team themselves have never looked at. My favourite book for understanding risk is “Waltzing with Bears”, which starts the first chapter with, “If a project has no risks, don’t do it.” It’s these new, risky aspects of the project that differentiate it from others and make it valuable in the first place!

For new and risky aspects of a project, the best thing to do is assume you got it wrong, and work out how quickly you can get feedback on how wrong you are.

Any new or unknown aspect of a project will need to be changed.

I was chatting to one of our analysts. “I can see this feature is in analysis at the moment,” I said. “Does that mean it’s the next thing we want the developers to do?”

“Oh, no,” the analyst said. “It’s only there because the analysis is quite complex. It’s all new stuff, so we’re having to be careful with it and it’s taking a bit of time. Once we get the analysis done, the development should be very easy, so we’ll do it later.”

“Oh, the development will be easy, I’m sure… but wouldn’t you like to find out what you did wrong now, rather than later, while it’s still fresh in your mind?”

The analyst smiled. The company was very much more used to Waterfall, and the idea that it was OK to get it wrong was something very new.

It’s OK to get it wrong, as long as you get feedback quickly, while the cost of change is still low. By working out which parts of a project are unknown or new, and targeting those first, we make small investments while the cost of change is still low.

Keep your options open – do the risky stuff first and keep tech debt low.

Anyone who’s run into me at conferences will know how much I love Real Options, and it’s really at the heart of the cost of change.

The only reason change costs more is because of the commitment that we already made. Chris Matts describes technical debt as an “unhedged call option”. Edit: while Chris came up with the metaphor, it was Steve Freeman who described it. He says, “You give someone the right to buy Chocolate Santas from you at 30 cents each. That’s fine, as long as the price of chocolate stays low. As soon as it goes up, you still have to pay to make the Santas, and now you’re in trouble and your company is going bust, because you didn’t give yourself the option to get the chocolate somewhere else.”

Similarly, technical debt is absolutely fine until we’re called on to act, and act fast. At that point, we’re in trouble. This is the biggest reason for keeping the cost of change low – because it gives us the option for change, later. It’s a frequently-cited reason for replacing legacy projects – and, bizarrely, often forgotten when the pressure mounts and the business want their replacement app.

This isn’t helped by common practices of estimation and the associated promises, which often lead to that pressure building up in the first place. Rather than making these promises up-front, why not try the risky bits first? I often hard-code data so that I can get feedback on a new UI early, or I spike something out using a new library or framework, or connect to that third-party application just to see what the API is really like to use, or have a chat with the team writing that other system we’re going to need in June, so I can find out how communicative and receptive to feedback they are. Doing this means that we give ourselves the most time to recover from any unexpected discoveries, and we can worry about the more predictable aspects of a system later.

Once we’ve got spikes out of the way, adding tests to act as documentation and examples for any legacy code we’ve created, cleaning it up so it’s self-commenting, ensuring that architectural and modular components are properly decoupled, etc., all help us to stabilize the code. At the same time, the effort involved in creating stable code is itself an investment. If there’s a good chance that the code might be wrong, it could be worth getting feedback on that – knocking up integration tests, showing it to the business, testing it, getting it live – before it’s made stable.

That way, the commitment made is small, and the cost of change is low.

Just remember to clean up and keep it that way!

Update: Dan is currently writing about Spike and Stabilize and Ginger Cake as part of his “Patterns of Effective Delivery”. If you’re interested in finding out more, you might like to watch his Roots talk on the topics.